On 14 March 2017, the Graduate Workshop was pleased to welcome Dr Catriona Ellis of the University of Edinburgh whose recent research has examined how childhood was constructed or imagined in colonial South India in the 1920s and 1930. Since submitting her PhD in September 2016, Catriona has volunteered at Edinburgh’s Museum of Childhood. A departure from the more traditional primary sources of her thesis, the experience has provided a fascinating opportunity to engage with a completely different – and contested – form of material culture.

In her paper, Catriona looked principally at the Museum’s Indian collection. She considered what toys might reveal about Indian children and how toys might also reflect the experiences of children visiting India. What do they tell us about universal values of childhood? She illustrated her presentation with images of dolls, transparencies and an authentically Indian tak taki. But in many ways, it was the physical presence of a more contemporary Indian Barbie doll which she had bought for her own daughter, which allowed Catriona to illustrate just how contested a “toy” might be. Do we see “Jasmine” through the eyes of the child or the adult? Is the Barbie simply a reflection of what society dictates, or something which appeals directly to the child’s imagination? Perhaps she might become a vehicle for diverse kinds of nostalgia, connecting one generation with another, or providing a link with Empire? In a museum context, does the approach of a collector, or curator (a point picked up in the Question and Answer session), affect its representation and our perceptions?

The Museum, which was opened in 1955 by Councillor Patrick Murray (1908-1981), was one of the first of its kind. There are a number of non-British toys referred to in the Catalogues, but, frustratingly, provenances are often not recorded. Unfortunately, Murray’s passion for toys was not matched with an assiduous eye for their classification. Toys of Empire, however, clearly provide an identifiable grouping within the Museum’s collection. In 1987, Diana  Horne donated a pull along buffalo which her father had bought for her in India in the twilight days of Empire. Forty years on, she described it as “a lovely souvenir of our colonial days”, the buffalo evoking a palpable sense of imperial nostalgia. But a toy might have had a more didactic purpose. Catriona showed us examples of transparencies dating back to the late 19th century which appear to represent Indians in stereotypical terms. Arguably, they were produced to convey a certain cultural message to British children whether or not they lived in India. The Tak taki ,on the other hand, was an example of a toy which Indian children would have enjoyed. As it was pulled along, its wheel drove a beating drum, giving the toy its distinctive name. Catriona showed us an image of an example, probably dating to the 1880s, which had been brought back to Scotland, and known in the donor family as Polly’s Indian or Chinese Toy: a distinctly Indian toy, traditionally used by Indian children, but in this context a vehicle (literally perhaps) for a sense of imperial nostalgia.

Horne donated a pull along buffalo which her father had bought for her in India in the twilight days of Empire. Forty years on, she described it as “a lovely souvenir of our colonial days”, the buffalo evoking a palpable sense of imperial nostalgia. But a toy might have had a more didactic purpose. Catriona showed us examples of transparencies dating back to the late 19th century which appear to represent Indians in stereotypical terms. Arguably, they were produced to convey a certain cultural message to British children whether or not they lived in India. The Tak taki ,on the other hand, was an example of a toy which Indian children would have enjoyed. As it was pulled along, its wheel drove a beating drum, giving the toy its distinctive name. Catriona showed us an image of an example, probably dating to the 1880s, which had been brought back to Scotland, and known in the donor family as Polly’s Indian or Chinese Toy: a distinctly Indian toy, traditionally used by Indian children, but in this context a vehicle (literally perhaps) for a sense of imperial nostalgia.

By virtue of its size and the evident zeal of its collector, the Lovett collection represents a significant part of of the Museum’s overall collection. In the late 19th/early 20th century Edward Lovett (1852-1933), a London toy collector, amassed 670 dolls from all over the world. Originally, they were sold to the Museum of Cardiff but in 1961 they were given on permanent loan to the Museum of Childhood. Lovett’s interest lay principally in Japanese and Chinese dolls but his collection also contains several Indian, mostly, rag dolls. Catriona argued that the Lovett dolls represent “a material representation of (Lovett’s) understanding of racial and cultural hierarchies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries”. As a collector, Lovett openly played down the artistic significance of the dolls, and implicitly suggested that they revealed gradations of cultural sophistication. But, in his later writings, he appeared to be alive to the enduring commonality of the toy, and the universality of play. Catriona considered the seventeen dolls in the Lovett collection. With one exception, they are relatively simple rag dolls but, as Catriona suggested, their simplicity might have provided greater scope for a child’s imagination.

By virtue of its size and the evident zeal of its collector, the Lovett collection represents a significant part of of the Museum’s overall collection. In the late 19th/early 20th century Edward Lovett (1852-1933), a London toy collector, amassed 670 dolls from all over the world. Originally, they were sold to the Museum of Cardiff but in 1961 they were given on permanent loan to the Museum of Childhood. Lovett’s interest lay principally in Japanese and Chinese dolls but his collection also contains several Indian, mostly, rag dolls. Catriona argued that the Lovett dolls represent “a material representation of (Lovett’s) understanding of racial and cultural hierarchies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries”. As a collector, Lovett openly played down the artistic significance of the dolls, and implicitly suggested that they revealed gradations of cultural sophistication. But, in his later writings, he appeared to be alive to the enduring commonality of the toy, and the universality of play. Catriona considered the seventeen dolls in the Lovett collection. With one exception, they are relatively simple rag dolls but, as Catriona suggested, their simplicity might have provided greater scope for a child’s imagination.

Catriona finished with Pachisi, a 16th Century Indian Board game, which is said to ha ve originated in the Mughal Court of Fatepur Sikri. This complex adult board game, played exclusively by the upper castes, was later appropriated and simplified by the British. It was the forerunner of Ludo. Catriona showed us an example of the original, acquired in the 1920s and used by the donor’s family until the 1970s. The evolution and packaging of the game may well tell us more about the attitudes of adults than the play of children.

ve originated in the Mughal Court of Fatepur Sikri. This complex adult board game, played exclusively by the upper castes, was later appropriated and simplified by the British. It was the forerunner of Ludo. Catriona showed us an example of the original, acquired in the 1920s and used by the donor’s family until the 1970s. The evolution and packaging of the game may well tell us more about the attitudes of adults than the play of children.

Toys occupy contested territory but provide a further dimension to our understanding of childhood. Collecting strategies add an extra later of complexity, delineating, even directing our perceptions of childhood. This well attended presentation stimulated animated discussion. We wish Catriona well with her continuing research at the Museum of Childhood and look forward to seeing her again at the Graduate Workshop.

___________________

Our next Graduate Workshop will take place on Tuesday 4 April when Grant Collie of Massey University, New Zealand will be speaking on “Emigrant Scottish Miners in the NZ Tunnelling Company: 1916-1919”

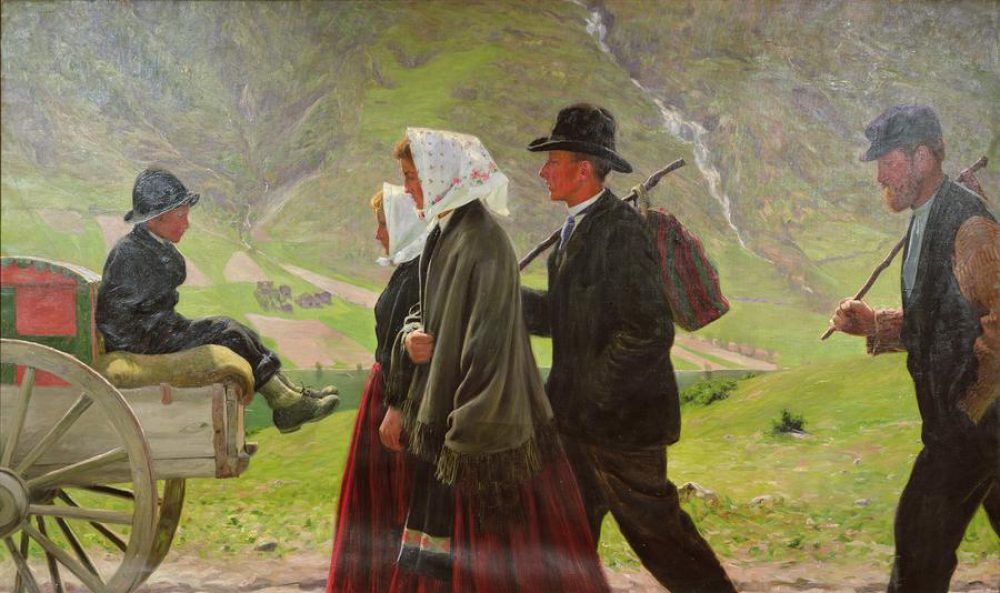

Grant tells the story of 62 Scottish members of the New Zealand Tunnelling Company who emigrated to New Zealand in 1880-1914. Previously, many had worked as miners in the central belt of Scotland. But who were they? And what were the reasons for their emigration?

The Workshop will take place at 1 pm in G 16 of the William Robertson Wing of the School of History, Classics and Archaeology (Doorway 4).

Everyone is most welcome to attend.

The Scottish cemetery, which was established in 1820, is associated with the nearby St Andrews Church. Its graves and memorials provide an historical snap shot of the many Scots living and working in Kolkata during the 19th and 20th centuries. Many graves were constructed and designed by Scottish sculptors. By 2008, however, when the team began conservation work, the cemetery had become extremely overgrown.

The Scottish cemetery, which was established in 1820, is associated with the nearby St Andrews Church. Its graves and memorials provide an historical snap shot of the many Scots living and working in Kolkata during the 19th and 20th centuries. Many graves were constructed and designed by Scottish sculptors. By 2008, however, when the team began conservation work, the cemetery had become extremely overgrown.

Horne donated a pull along buffalo which her father had bought for her in India in the twilight days of Empire. Forty years on, she described it as “a lovely souvenir of our colonial days”, the buffalo evoking a palpable sense of imperial nostalgia. But a toy might have had a more didactic purpose. Catriona showed us examples of transparencies dating back to the late 19th century which appear to represent Indians in stereotypical terms. Arguably, they were produced to convey a certain cultural message to British children whether or not they lived in India. The Tak taki ,on the other hand, was an example of a toy which Indian children would have enjoyed. As it was pulled along, its wheel drove a beating drum, giving the toy its distinctive name. Catriona showed us an image of an example, probably dating to the 1880s, which had been brought back to Scotland, and known in the donor family as Polly’s Indian or Chinese Toy: a distinctly Indian toy, traditionally used by Indian children, but in this context a vehicle (literally perhaps) for a sense of imperial nostalgia.

Horne donated a pull along buffalo which her father had bought for her in India in the twilight days of Empire. Forty years on, she described it as “a lovely souvenir of our colonial days”, the buffalo evoking a palpable sense of imperial nostalgia. But a toy might have had a more didactic purpose. Catriona showed us examples of transparencies dating back to the late 19th century which appear to represent Indians in stereotypical terms. Arguably, they were produced to convey a certain cultural message to British children whether or not they lived in India. The Tak taki ,on the other hand, was an example of a toy which Indian children would have enjoyed. As it was pulled along, its wheel drove a beating drum, giving the toy its distinctive name. Catriona showed us an image of an example, probably dating to the 1880s, which had been brought back to Scotland, and known in the donor family as Polly’s Indian or Chinese Toy: a distinctly Indian toy, traditionally used by Indian children, but in this context a vehicle (literally perhaps) for a sense of imperial nostalgia. By virtue of its size and the evident zeal of its collector, the Lovett collection represents a significant part of of the Museum’s overall collection. In the late 19

By virtue of its size and the evident zeal of its collector, the Lovett collection represents a significant part of of the Museum’s overall collection. In the late 19 ve originated in the Mughal Court of Fatepur Sikri. This complex adult board game, played exclusively by the upper castes, was later appropriated and simplified by the British. It was the forerunner of Ludo. Catriona showed us an example of the original, acquired in the 1920s and used by the donor’s family until the 1970s. The evolution and packaging of the game may well tell us more about the attitudes of adults than the play of children.

ve originated in the Mughal Court of Fatepur Sikri. This complex adult board game, played exclusively by the upper castes, was later appropriated and simplified by the British. It was the forerunner of Ludo. Catriona showed us an example of the original, acquired in the 1920s and used by the donor’s family until the 1970s. The evolution and packaging of the game may well tell us more about the attitudes of adults than the play of children. in G 16 (in the William Robertson Wing of the School of History Classics and Archaeology)

in G 16 (in the William Robertson Wing of the School of History Classics and Archaeology)