Sean Murphy from the University of St Andrews spoke to the Diaspora Studies Graduate Workshop on Tuesday 1 November. Sean has a particular interest in the relationship between the Scots language and British imperialism. He is a graduate of the Universities of Glasgow and Oxford, and will shortly submit his PhD thesis at the University of St Andrews. We were delighted to welcome back Sean.

______________________

The new circumstances under which we are placed, call for new words, new phrases, and for the transfer of old words to new objects. An American dialect will therefore be formed.

Thomas Jefferson 16 August 1813

In the early decades of the 19th century, Thomas Jefferson argued that the growing United States of America, a nation of considerable size and cultural diversity, required a language to express all ideas. Would new words and new phrases “adulterate” the English language? Had the language of Burns “disfigured” the English language? Did the Athenians consider the Doric, the Ionian, the Aeolic, and other dialects, as disfiguring or as beautifying their language?” Jefferson thought the latter. Developing an analogy based on the richness of the Greek language, he argued that a variety of dialects enriched a language. The learned writers of the contemporary Edinburgh Review, who eschewed new words were, in his view, mistaken.

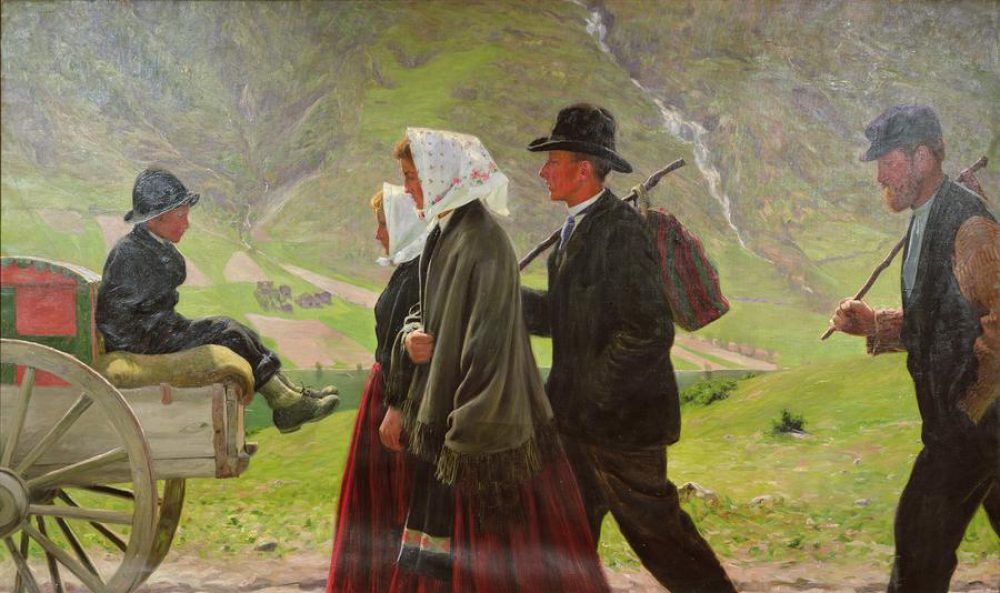

Sean Murphy used the words of Jefferson as both the introduction and cornerstone of his presentation. Jefferson had expressed the desire to “enlargen our  employment of the English language”. Moreover, a dignified American dialect was comparable to the Scots of Robert Burns whose writing had been readily available in the young United States of American from the 1790s. The poetry of Burns, Sean argued, fostered a sense of nostalgia, in emigrant Scots.

employment of the English language”. Moreover, a dignified American dialect was comparable to the Scots of Robert Burns whose writing had been readily available in the young United States of American from the 1790s. The poetry of Burns, Sean argued, fostered a sense of nostalgia, in emigrant Scots.

The work of two Scots/Irish poets provide an important insight into the social and diasporic world of Scots/Irish. David Bruce from Pennsylvania was a first generation emigrant who may have had roots in the north-east of Scotland, possibly in Caithness. A contemporary of Burns, his poetry expressed the post-colonial political concerns of a Scots/Irish diaspora. Bruce defended the Scottish Irish community which had been blamed for the so called Pennsylvania “whiskey rebellion of 1794”. Fiercely anti Jacobin, his work reflected an earlier age and showed a Scottish pride in rationality.

Robert Dinsmore of New Hampshire, was a third generation emigrant Scots/Ulsterman. If Bruce was a Scottish American, then it might be argued that Dinsmore was an American Scot. Sean’s readings of Dinsmore’s poetry tended to suggest that the vowel sounds of a third generation Scot might have developed, or, in any event, have been different from the Scots American of Bruce. Dinsmore looked to the past and made a connection between his ancient Irish ancestors and the tribes of the native American Indians. He was more of a rustic bard. Both poets – Bruce in more pastoral vein – were influenced by the poetry of the elder Alan Ramsay, of Gentle Shepherd fame, who was known for his use of the Scottish vernacular two generations before Robert Burns. Nostalgia, perhaps even exoticism, were the hallmarks of these poets. If the English had crafted Athenian, then the Scots excelled at the Doric.

A wide-ranging discussion considered the publication and marketing of the poems and the extent to which other diasporic groups may have been represented in contemporary periodicals.

_________________________

Please note:

The Graduate Workshop originally scheduled for Tuesday 15 November, has been cancelled.

Unfortunately, our speaker, Micheal Hopkirk of the University of Dundee, is indisposed. Michael was due to speak on “Highland Adventurers to the Caribbean: Estimating the Scale of Highland-Caribbean Economic Migration, 1780-1830”

Our next Graduate Workshop will now take place on Tuesday 29th November (further details below)

Alastair Learmont

The Scottish cemetery, which was established in 1820, is associated with the nearby St Andrews Church. Its graves and memorials provide an historical snap shot of the many Scots living and working in Kolkata during the 19th and 20th centuries. Many graves were constructed and designed by Scottish sculptors. By 2008, however, when the team began conservation work, the cemetery had become extremely overgrown.

The Scottish cemetery, which was established in 1820, is associated with the nearby St Andrews Church. Its graves and memorials provide an historical snap shot of the many Scots living and working in Kolkata during the 19th and 20th centuries. Many graves were constructed and designed by Scottish sculptors. By 2008, however, when the team began conservation work, the cemetery had become extremely overgrown.

On 28 February 2017, we were delighted to welcome Dr Maria Alonso Alonso to the Diaspora Studies Graduate Workshop. Maria obtained her PhD from the University of Vigo in 2014 and is currently based at the University of St Andrews where she holds a a Xunta de Galicia International Postdoctoral Fellowship. Her work focusses on the Galician diaspora. She has published widely in academic journals; her output also includes short stories, poetry and a novel in the Galician Language. Her most recent book entitled Transmigrantes Fillas de Precareidade (“Transmigrants , Daughters of Precariousness”), published by Axourere in 2017, challenges an over positive image of migration in order to highlight the feelings of vulnerability experienced by her own, younger generation. In a stimulating paper Maria, explored the interconnected themes of crisis, migration and precariousness.

On 28 February 2017, we were delighted to welcome Dr Maria Alonso Alonso to the Diaspora Studies Graduate Workshop. Maria obtained her PhD from the University of Vigo in 2014 and is currently based at the University of St Andrews where she holds a a Xunta de Galicia International Postdoctoral Fellowship. Her work focusses on the Galician diaspora. She has published widely in academic journals; her output also includes short stories, poetry and a novel in the Galician Language. Her most recent book entitled Transmigrantes Fillas de Precareidade (“Transmigrants , Daughters of Precariousness”), published by Axourere in 2017, challenges an over positive image of migration in order to highlight the feelings of vulnerability experienced by her own, younger generation. In a stimulating paper Maria, explored the interconnected themes of crisis, migration and precariousness.

On 12th January 2017, the Graduate Workshop welcomed Jennifer McCoy of Federation University, Australia. Jennifer is a part time first-year PhD student who currently combines research with teaching. Her doctoral research considers the contribution made by immigrant Scots in the development of Eastern High Country Victoria in the mid to late 19th century. Family history has provided the stimulus for Jennifer’s formal academic research and, in her own words, has led to her asking “so many questions that (have gone) beyond the usual genealogical study of births, marriages, deaths and people connections”. Her presentation considered the “loose ends” which have inspired her project and the lines of enquiry which they suggest.

On 12th January 2017, the Graduate Workshop welcomed Jennifer McCoy of Federation University, Australia. Jennifer is a part time first-year PhD student who currently combines research with teaching. Her doctoral research considers the contribution made by immigrant Scots in the development of Eastern High Country Victoria in the mid to late 19th century. Family history has provided the stimulus for Jennifer’s formal academic research and, in her own words, has led to her asking “so many questions that (have gone) beyond the usual genealogical study of births, marriages, deaths and people connections”. Her presentation considered the “loose ends” which have inspired her project and the lines of enquiry which they suggest. employment of the English language”. Moreover, a dignified American dialect was comparable to the Scots of Robert Burns whose writing had been readily available in the young United States of American from the 1790s. The poetry of Burns, Sean argued, fostered a sense of nostalgia, in emigrant Scots.

employment of the English language”. Moreover, a dignified American dialect was comparable to the Scots of Robert Burns whose writing had been readily available in the young United States of American from the 1790s. The poetry of Burns, Sean argued, fostered a sense of nostalgia, in emigrant Scots.